Day 29. Newport Rd

Day 30. City Rd

Day 31. Albany Rd

Day 32. Adamsdown

Day 33. Cardiff Central

Day 34. Teruel

Day 35. Albacete

Day 29. Newport Rd

Day 30. City Rd

Day 31. Albany Rd

Day 32. Adamsdown

Day 33. Cardiff Central

Day 34. Teruel

Day 35. Albacete

Day 22 (1). Roath

Day 22 (2). Newport Rd

Day 22 (3). Albany Rd

Day 22 (4). Albany Hotel

Day 23 (1). Clifton St

Day 23 (2). Crwys Road

Day 24 (1). Splott Bridge

Day 24 (2). Newport Rd

Day 24 (3). Clifton St

Day 24 (4). City Rd

Day 25 (1). Cardiff

Day 25 (2). Cardiff

Day 25 (3). Cardiff

Day 25 (4). Cardiff

Day 25 (5). Newport Rd

Day 25 (6). Riverside

Day 26 (1). Newport Rd

Day 26 (2). Albany Rd

Day 27 (1). Albany Rd

Day 27 (2). Albany Rd

Day 27 (3). Albany Rd

Day 28. Albany Rd

Day 15. Albany Rd

Day 16. Cardiff Bay

Day 17. Cardiff Bay

Day 18 (1). Butetown

(2) . Butetown

(3) Butetown

(4). Butetown

Day 19 (1). Cardiff City Centre

(2). Cardiff City Centre

Day 20. Severn Bridge (Aust Ferry)

Day 21. Albany Rd

Day 8. Albany Rd

Day 9. Albany Rd

Day 10. Albany Rd

Day 11. Cardiff Bay

Day 11 (2). Cardiff Bay

Day 12. Cardiff City Stadium

Day 13. Albany Rd

Day 14. Albany Rd

Day 1. Cardiff Bay

Day 2. Cardiff Bay

Day 3. Cardiff Bay

Day 4. Cardiff Bay

Day 5. Dave Grooveslave

Day 6. Albany Rd, Cardiff

Day 7. Albany Hotel, Cardiff

Albany Rd

Our civilisation sits upon a powder keg. Not only are depraved lunatics holding the matches, but they are fucking around dangerously close to the barrel. The seeds of hatred are germinating. Time’s precious hands slip ever closer to… Something.

There are no barricades — only the pernicious squawking of soft-bellied liberals. Disneyfied sludge seeps over the entire arena like a heavy fog of raw Ether. It has taken only a few generations to forget…

Four friends stand next to the edge of a high cliff. One of the friends holds and points a gun at the three others. The gun-holder politely tells the other three that they must decide together which they prefer: to die by being shot or by throwing themselves off the cliff?

Two of the friends begin to deliberate, gratefully. One praises the merits of being shot and dying instantly with no pain. The other speaks thoughtfully about the spectacular view they would enjoy as they fell to the jagged rocks far below.

They turn to the third friend, who has been silent up until this point and whom the final decision on the fate of the three friends now rests with.

This friend remains silent, their whole body shaking as the muscles of their face visibly contort with anger and frustration — eyes moving slowly from the barrel of the gun to meet the eyes of the fourth friend holding the weapon.

“Come on,” the three others tell their silent friend, “people died so that you could vote!”

END

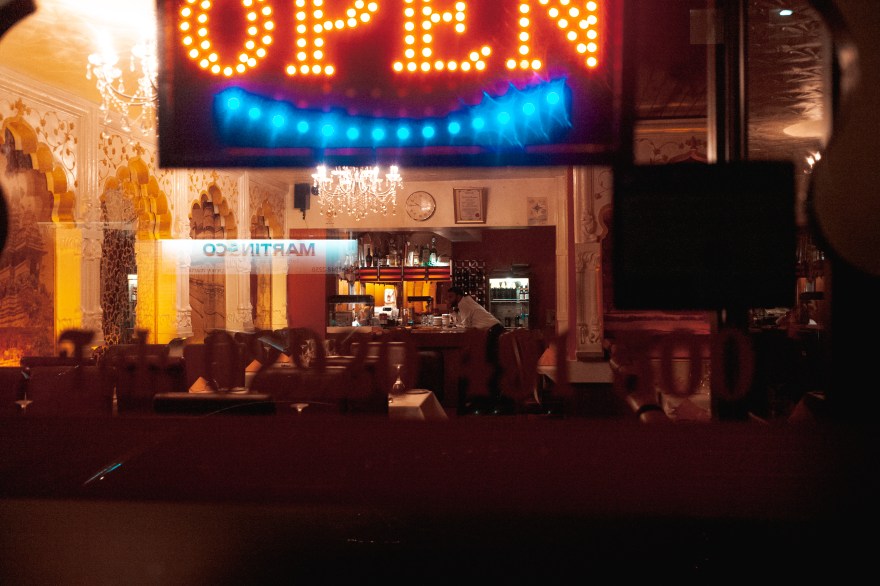

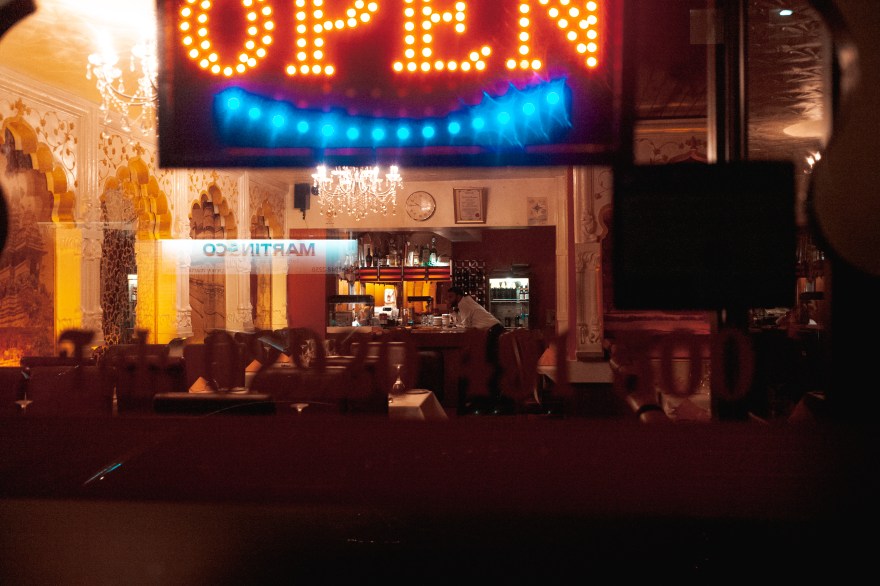

Exhibited at the Andrew Buchan Bar, Cardiff. Oct 10th – Nov 7th

We were close, but not enough to walk. The carpark was still and in shadow apart from a few scattered blocks of golden haze cast between industrial objects reaching into the sky above the coastline. We wandered the pedestrian walkway expectantly, with only the occasional drone of a passing vehicle off in the distance disturbing our general chitchat.

On the ship, I had struck up a conversation with the man. He had also been in the waiting room. I asked if he knew anything regarding getting to Paris from Calais. He was hitchhiking to Groningen from London and wondered if I knew a good place to pick up a lift. We crossed the full expanse of the tarmac and metal alloy, during which time the hitchhiker seemed to be troubled by the weight of his bag and I was mildly irritated by my decision not to have a look around the terminal building first… Shouldn’t go back.

We passed a roundabout and went through an underpass then came to another roundabout. The hitchhiker lagged behind. “Are you going that way? I think I need to go this way,” he said. My guess was to follow the road sign for the city centre but I was disorientated by my phone’s GPS, which was not working. “The port must be a dead zone,” I assumed. I paced back and forth with indecision. A few dozen yards in one direction before changing my mind and walking in the other direction. I could see the hitchhiker a few hundred yards ahead of me that way had stopped with his rucksack at his feet, which he was making adjustments to. “Maybe it’s something to do with the network provider?”

The landscape to the south was dominated by a huge hanger-like building covered in shining bronze-tinted metallic cladding. I used it as a landmark to asses the best route. This way was cut-off by a river and the nearest bridge was far. I elected instead for the long, straight road adjacent to the ferry port. Along it, I studied the grounds of the hanger building. The huge swathe of grass and concrete looked shabby from disuse. Bits of glass, piles of rubble and other debris covered the site, where a colony of rabbits had made their home too.

At the end of the road was a roundabout. On the other side of the junction, an emergency vehicle of some sort was parked with three uniformed persons standing around it. Despite having half a thought on asking them for directions, I didn’t pay enough attention to whether they were police or ambulance or something else to do with the port. The direction went through an industrial estate, where the entrance gates for the hanger building were located at the top of. On the other side of the gates, the engine of a white fiesta idled with its driver-side door open. I passed no one going through the industrial estate but thought I saw the hitchhiker distantly ahead of me, now without a rucksack.

Eventually, I arrived at an urban area on the city’s outskirts and could see an ornate clocktower in the distance climbing above all the other buildings surrounding it. Two people stood in mild discussion in the forecourt of a petrol station and a woman carrying shopping bags gave me a fleeting curious look as she passed me by. Moving in the general direction of the clocktower I walked the terraced streets along a main road comprised of closed or empty shops and a few small, dirty looking brasseries and bars, also not open. Each had the chipped, faded paint on the windowsills or around their doorways. I walked under a black sign above a doorway with bold yellow letters spelling “SEX SHOP” thrusting out into the street. A man stood propped up against a lamppost, clasping a pastry bag in one hand. As I got closer I noticed his hands and face were covered in dirt or soot and his eyes stared past me vacantly. He seemed to be waiting for a bus or for someone to come out of one of the houses.

I arrived at the hotel and I immediately arranged a taxi for 11.45 the following morning to the train station. I was told that the person on the desk tomorrow would take care of it. I mentioned the difficulty in getting from the ferry terminal to the reception person, who was aghast with disbelief. There was some problem with the system which meant that she had to go through the process of printing my bill several times. When I enquired about dining recommendations, she quickly produced the menu of a brasserie just around the corner from the hotel, which she enthusiastically pressed on me. I had passed the brasserie on my way in. It stood out, as it was the only business I had actually seen open.

Studying the menu in the brasserie’s window I instantly gauged all the telltale signs of a tourist trap. I was about to head in, amused at the idea of the 14€ Welsh rarebit, when something landed with a soft thud just behind my shoulder blade. One of the local gulls had seen fit to grace me with a welcome gift. An elderly group of three gave me pitied looks of embarrassment while also giving me a wide berth.

Soap and toilet paper in the small sink of my hotel bathroom seemed to clear up the worst of it, so leaving the jacket to dry, I went for dinner. At the end of the meal, the waiter appeared in front of me presenting a dessert menu, which I declined. An elderly British couple finished their dessert and eventually managed to get the attention of the waiter to ask for the bill.

“Mursi bhoo c-hoo” the woman of the couple said ceremoniously, followed by a small, apologetic laugh.

In the morning I went down for the continental breakfast, which I had paid extra for on check-in. I was confronted by the morning receptionist as I selected my breakfast items. His shoulders were stooped and his face was rough like it had been hacked from cheap MDF. In French, he politely asked to see my room card. He spoke with a thick accent that sounded American. His mouth was small with thin lips surrounding it, and he mostly spoke through his bottom teeth.

After breakfast, I went to the front desk to enquire about the taxi. I waited, rang the service bell, but no one appeared. I came back down after packing. This time the man was on the phone. He hung up and before I could say anything asked if I was the person who had booked the taxi. He had been on the phone with the company and they were sending one right away. This was earlier than I had ordered, but better to arrive in plenty of time.

I waited in the hotel foyer, reading the morning news and watching the man shuffle around attentively from deed to deed. After my second cigarette, there was still no sign of the taxi. It was nearly 11.45. The man was understanding and contacted the company. It would be another 15 minutes. I doubted that, and besides, that would be too late. He called another company, which was similarly indisposed. He was lost for an explanation. The man’s gaunt face then became dishevelled with concentration as he made further enquiries on the reception computer. His suggestion was to take a train from the city centre station to the station where the train to Paris would leave. I thanked him, maybe sardonically, and left with my things.

The streets were just as bare as the previous evening as I quick marched to the station. A homeless man sitting outside a bakery greeted me, which I halfheartedly replied to, making it clear I was in a rush.

At the station, I attempted to purchase a ticket from the automated ticket machine. But the English instructions were only partly translated it seemed, with the ticket choices still in French, which I couldn’t comprehend. I took the receptionist’s advice and didn’t bother getting one. “They never check,” he told me confidently.

I went to the platform where he said the train would be. The screen in the station had shown the train but didn’t say which platform. I checked another platform, but this wasn’t right either. The third platform I came to was correct, with the train already there waiting. The margin was fine but I should arrive with a few spare minutes before for the train to Paris. The man in the hotel had assured me that the train left from the opposite platform of the one I would arrive on.

I sat nervously in a chair in one of the rear carriages where the train attendant seemed to be hovering around in his navy uniform with a red stripe through his conductor’s hat. He passed once, saying only, “Bonjour,” and spent the rest of the journey talking to another person in the same carriage. As the train snaked through the desolate peripheries of the town, I paid particular attention to the security fencing; three layers thick, intermittently interrupted by guard towers and security gates, which ran for miles flanking either side of the train tracks away from Calais.

As part of an ongoing photo project, I recently paid a second visit of 2019 to Catalonia. This time I was travelling north up the coast from Barcelona to the small seaside-town of Malgrat de Mar.

The purpose of the trip was to meet up with British-born artist Rob McDonald, who is based in Catalonia and is the creator of the community memorial campaign, Solidarity Park. The project commemorates an incident involving volunteers of the International Brigade, which took place at the height of the Spanish Civil War almost exactly 82 years to the day of our meeting.

I was greeted warmly by Rob at his studio and exhibition space in Malgrat de Mar where I was also introduced to Chris, another British expat who has lived for many years in Catalonia and is active in relevant circles. We were then joined by Paco, a local politician and a supporter of the Solidarity Park project.

Together we were heading a further 15 minutes up the coast to the town of Blanes where a boat had been arranged to take us to a site approximately 2 kilometers off the coast of Malgrat de Mar.

The significance of this site was that it is the location of the wreckage of the Spanish liner, the MV Ciudad de Barcelona, which was sunk on May 30th, 1937. The ship had been travelling from Marseille to Spain carrying several hundred International Brigaders as well as military cargo for the Republican war effort when it was torpedoed by an Italian submarine belonging to General Franco’s nationalist forces.

We arrived at the town’s harbour where we met with Noria, a local secondary school English teacher who had been responsible for arranging the boat trip with her father (also named Paco) who was to be ship’s Captain during our short voyage.

As we left the harbour in our modest fishing boat, Paco pointed to me the area further along the coast where the ship had initially been fired upon by the Italian submarine. The ship had received several warnings of enemy submarine activity in the area and was tightly hugging the coastline in case of attack. This first torpedo turned out to be a dud, missing its target and ending up ashore on the next coastal town over.

The pleasant weather of late spring had brought many of those on board up on deck despite orders to stay below. The Non-Intervention Agreement had made the process of volunteers entering into Spain a clandestine operation. Those on board represented a truly Internationalist force of volunteers from across the globe, including many Americans and Canadians, as well as some Australians and New Zealanders mixed with innumerable European nationals; all hoping to reach Spain to play their part in halting the rising threat that fascism posed to the world. Tragically, however, many of those volunteers would never manage to set foot on Spanish soil.

Just before 3 p.m. the Italian submarine fired a second torpedo, which plunged into the ship’s aft close to the engine room where it exploded; killing many instantly and trapping many more inside.

Chaotic scenes ensued. Volunteers darted around looking for life jackets as many jumped overboard without. The stern of the rapidly sinking ship was disappearing beneath the waves. Two of the lifeboats at the stern of the ship were underneath the water before they could be freed, another two were successfully launched while one overturned – throwing its occupants into the water and then crashing down on top of them. The hundreds of people now in the water clambered onto any piece of debris they could find or quickly swam away to escape the force of the sinking ship dragging them below with it.

The ship was completely submerged in a matter of minutes. Around the area of the sunken vessel, the crystal blue of the Balearic Sea was tinted crimson as bodies and flotsam bobbled on its oily surface. Many witness accounts of the incident tell how as the ship sank voices of volunteers still trapped within the boat could be heard singing ‘The Internationale’ – the anthem of the International Brigades.

According to prominent researcher Alan Warren, four of the 60 crew and 187 of the 312 passengers died. An exact number of volunteers is difficult to give due to them being smuggled on board. At least 23 of the survivors of the sinking of the Ciudad de Barcelona would later be killed fighting in the civil war.

My interest in this tragic incident was triggered by an account from Welshman, Alun Menai Williams of Gilfach Goch, who was one of a handful of Welshmen aboard the ship that day. They were; Harold Dobson of Blaenclydach, Alwyn Skinner of Neath, Emlyn Lloyd of Llanelli and Ron Brown of Aberaman, all of who survived. According to Williams, there was also an unknown man from Swansea aboard the ship who drowned.

For me, as compelling as Williams’ account of the sinking was, what I found just as compelling was his story leading to getting aboard the Ciudad de Barcelona. Having reached the Pyrenees, he had been arrested before reaching the border with a party of other volunteers aiming to cross into Spain. Williams had been in charge of the group’s money supplied by the French Communist Party in Paris. Having money meant he was able to avoid vagrancy charges and a prison sentence. Despite not being charged, Williams was ordered to return to the UK and was escorted by French authorities all the way back to Paris. Deciding against returning to the UK, Williams then attempted to reach Spain by travelling to Marseilles in hope of making contact with people who could aid him in doing so. Failing to make any contacts, and without any money, he was forced to finally return to Britain.

Upon arriving in the UK, Williams deliberated for a short period of time then headed back to the Communist Party headquarters in London before making his second trip into France. He eventually made his way south; this time to Bordeaux, where he spent a month waiting to be shipped to the Basque country. However, this became impossible as Franco’s army took over control of the Basque region. At this point, himself, as well as a large group of other volunteers who were also attempting to reach Spain via the Basque area, were sent to Marseille where the 200-250 or so volunteers were smuggled onto the Ciudad de Barcelona.

Williams had been one of those who opted to jump overboard. He describes his fear during the two hours he was in the water, a feeling described by many other witness accounts. Their ordeal continued as a Republican plane dropped depth charges close to the survivors in an attempt to hit the submarine; the force of the underwater explosions thrashing them around in the water. The confusion at this time was so much so that some believed it to be an enemy plane and huddled in terror thinking it was about to strafe their boat as it flew low over the water attempting to attack the submarine.

Survivors were eventually picked up by locals from Malgrat de Mar in fishing boats then taken ashore. Many describe the kindness shown to them by the locals who took care of them and their surprise to find out they were in fact, anarchists.

At this time, relations between the communists and the anarchists were fractious following the conflict between the two groups during the ‘May Days’ fighting earlier that same May. Volunteers had been told that should they be discovered by anarchists they would be shot for being aligned with the communists. The reality of how they were treated by the anarchist fishermen and locals of Malgrat de Mar compared to their perceptions demonstrates the turmoil of the political climate within the Republican side of the Spanish Civil War at that time.

After spending a night in Malgrat de Mar and being paid a visit by the Catalonian president, Lluis Companys, who wanted to apologise personally to the volunteers for the manner of their entrance into the war and welcome them. They were then transported to Barcelona under the cover of darkness to avoid being attacked by anarchists in Barcelona.

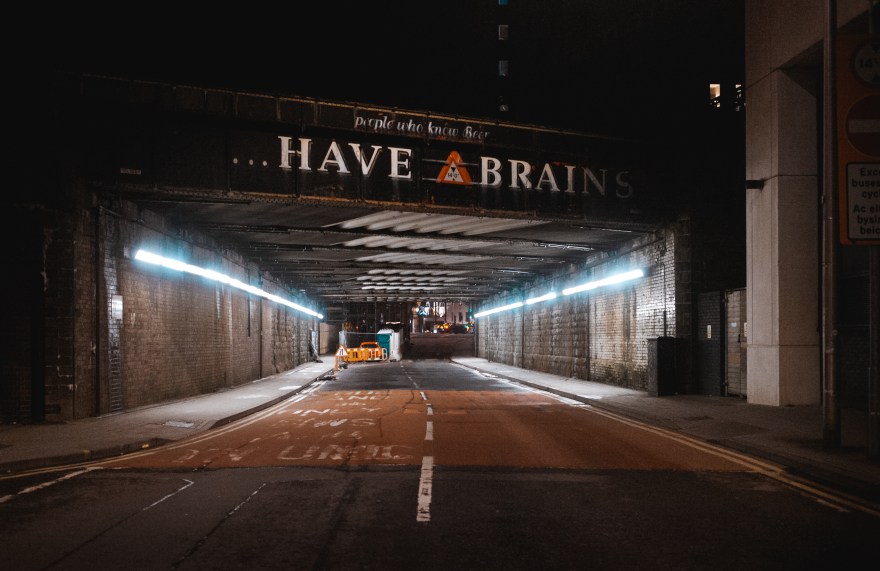

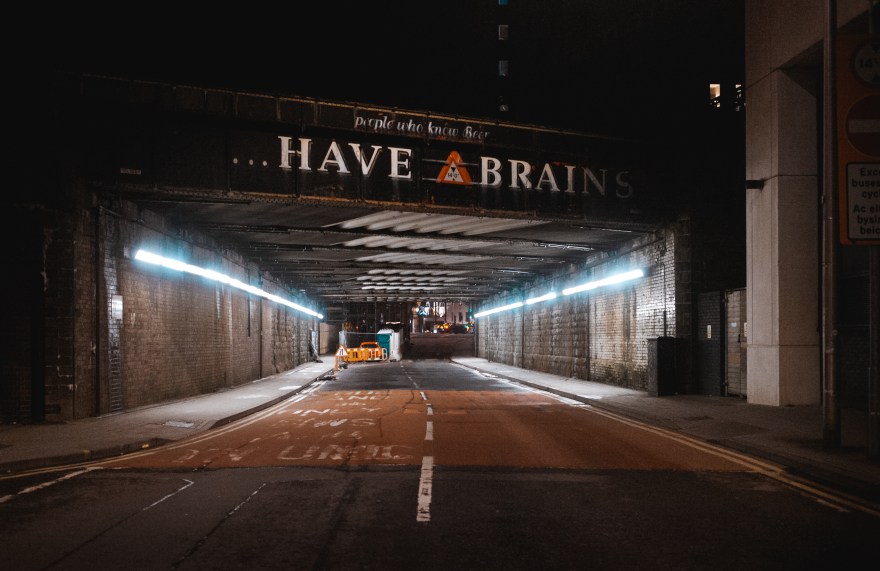

The volunteers were taken to the Karl Marx barracks where they were organised as a unit. Volunteers were then given the option to go home if they wished. Only one volunteer took the opportunity to do so. From then they were moved to the International Brigade headquarters in Albacete and entered into the fight for Spain.

Keep up to date with the Solidarity Park project through their Facebook page.

– Glyn